Well, here I am at 1:34am in the lab, waiting an hour so I can dump a little media onto a couple of plates and go home, so I thought maybe to pass the time I'd give you folks a real post for a change.

This is Fruit Genetics Friday #1b, because there's another #1 that covers the real basic stuff that isn't finished, and might never be. Frankly, basic genetics, while certainly cool, gets a little old to write a ton about, and I'm guessing my average reader remembers the really basic stuff. If you don't, feel free to ask questions. I won't think any less of you for it.

So on to the fruit genetics and one of my favorite topics, polyploidy:

One of the first major wrinkles one runs into when trying to understand the genetics of many fruit crops is polyploidy. Remember how people (and most animals and many plants) have two of each gene, one copy from each parent? That makes them diploid. That's sort of the basic model, and in the animal world it's the most common one. But in plants (and a few insects, reptiles, and amphibians), it's not uncommon to have more than the basic two sets of chromosomes, a condition called polyploidy ("di" meaning two, vs. "poly" meaning many, see?). Estimates are all over the place, but somewhere in the vicinity of 70% of plant species (angiosperms, anyway) are or have been polyploid at some point in their evolutionary past. An awful lot of crop species are polyploid, partly because one of the traits of polyploids is that they tend to be bigger than the their diploid counterparts, and in general bigger has been considered better when it comes to crop development.

For example, I started my career working with a diploid species, grapes, did my M.S. working with tetraploid blackberries (four sets of chromosomes), and now work with strawberries, which are octoploid (eight sets of chromosomes.) The cultivated strawberry is among the crops with the highest ploidy level, although there are blackberry species with as high as twelve sets of chromosomes (dodecaploid maybe? I get mixed up past ten. By the way, standard shorthand for these things is to use "x" to represent the basic chromosome set for a species, so a diploid is denoted as 2x, and tetraploid, 4x, etc.)

Just like diploids, when polyploids reproduce, they form eggs and pollen cells containing half the normal complement of chromosomes. This generally works pretty well if you've got an even number of sets of chromosomes, but it becomes a problem in odd-ploid plants. If you've got three copies of a particular chromosome, and the cells splits to form two pollen grain, what happens to the extra? The answer varies...sometimes one cell gets it and the other doesn't, sometimes it's just lost. The result, anyway, is reproductive cells that are complete mess a lot of the time. This results in sterile plants. A good example of this is the cultivated banana, which is triploid. Wild, diploid bananas are full of seeds, but because cultivated types can't produce viable sex cells, no fertilization takes place, and we get our nice soft, seedless bananas (although some one once told me that about one in every five or ten thousand bananas will contain a viable seed, the result of the off chance that a particular combination of chromosomes works out).

There are two types of polyploids, which are formed in two different ways. The simplest kind of polyploid is called an autoploid. In an autoploid, all the chromosome sets come from the same species. This can come from a spontaneous doubling in a vegetatively propagated plant (this happens when a cell basically makes a mistake mid-division and fails to divide after duplicating it's chromosomes). This has, for example, resulted in a handful of grape cultivars, such as 'Pierce', which was identified as a large-fruited shoot on an 'Isabella' vine. The other possible cause is the tendency of plants to occasionally produce sex cells with double the normal genetic complement, which are called "unreduced gametes". These unreduced gametes can also join to produce autoploids.

The other kind is called an alloploid. Alloploids have two or more different types of chromosomes, generally from ancestors of two or more different species. In octoploid strawberry we use the notation AAA'A'BBB'B' to indicate that the eight sets of chromosomes come in four different types, from four different ancestral species. Most crosses between species fail, resulting in sterile progeny (because unlike sets of chromosomes will not pair, it is next to impossible to form viable gametes, just like in an odd-ploid plant). However, if at some point the resulting plant doubles its genetic contents, the problem is solved. A new hybrid with genomes AB can't reproduce, because A chromosomes won't pair with B chromosomes. However, if AB becomes AABB, then the A chromosomes will pair with the other A chromosomes, and the B with the B, and fertility is restored, though frequently at less than perfect levels.

These potential problems with fertility are part of why artificial polyploids have been successful in only a relatively few cases. Even if a plant has big fruit, if it has sterility problems and has trouble actually producing that fruit, it's not going to be a hit. There are other problems, too, though they vary somewhat from species to species. In addition to fertility issues, polyploids tend to be less tolerant of cold, have less rugged shoots, and sometimes have disease issues as well.

Well, my labwork is calling. Next installment I'll look at inheritance in polyploids, and why it's so darn kooky. (I'm hoping to post a list of polyploid fruits here for you, but it's 2:30am, I've got lab work to do and a baby squawking, and I can't get the table HTML right, so it's got to wait.) I realize this may be a tad technical for some folks...like I said, let me know if there's something you're curious about and I didn't do a good job explaining it.

Anyway, good night, folks.

Update: Here's the little table I promised you folks. I really need to get me some fancy program to do my HTML...it's too tiring to do a big table, so this is hardly an exhaustive list, just some examples

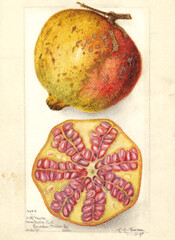

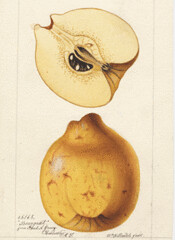

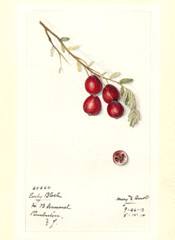

Update 2: The table is screwing things up, and my imperfect knowledge of HTML leaves me helpless when it comes to fixing it. So no more table. Sorry. I'd try to sort it out, but I'm way, way, too tired. So anyway, polyploids include blackberries, strawberries, sour cherries, European plums, bananas, blueberries, persimmons, some apples and mandarins, etc.

Labels: Fruit Genetics Friday, genetics