Fruit in Korea

I never reported back on my trip to Korea, mostly, I guess, because I hadn't reported back on anything here in months until very recently. But rest assured that I did go, and I did come back, and I did eat fruit while I was there.

Most of what I encountered was not overly exotic, although I did get to try the bokbunja that was recommended in the comments. This is a wine made from Rubus coreanus the Korean black raspberry. It was tasted about like what you'd expect from a black raspberry wine, but with a more substantial kick than I'd anticipated. (Of course, it was followed immediately by a couple of beers at a noraebang, so that might have had something to do with it). I thought it was pretty good. Apparently it also helps with impotence and sexual stamina, though neither was really an issue on this trip.

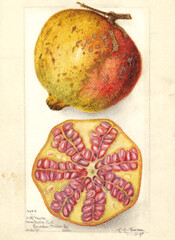

We also had hallabong, a relatively expensive but very tasty citrus fruit grown primarily on Jeju Island. It's vaguely tangelo-like, released from a Japanese breeding program in the 1970's (they called it Dekopon, but the Korean ones are named for a mountain on Jeju). I've seen a couple variations, so I'm not 100% confident in the pedigree, but the most probable seems to be:

Hallabong = Kiyomi x Ponkan

Kiyomi = Miyagawa x Trovita

Miyagawa = Citrus unshiu

Trovita = Citrus sinensis

Ponkan = Citrus reticulata

(Citrus unshiu x Citrus sinensis) x Citrus reticulata.

(For those unfamiliar with the Latin binomials, sinensis is the sweet orange, reticulata is mandarin/tangerine, and unshiu is the satsuma or mikan.

Anyway, very good. Unfortunately, I didn't get any pictures of it.

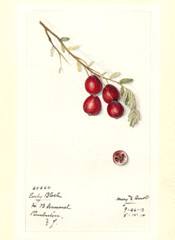

I did however get pictures of jujube (from a street market in Suwon):

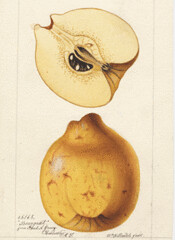

And some asian pears, apples, and kumquats:

(I don't know what variety of apples they were, but it seemed to be the same variety everywhere. I had one and it was pretty uninspiring).

And some strawberries (there's also a few oranges and melons hiding in there):

(This seemed to be the only way strawberries were sold in Korea–in big styrofoam boxes. I think these were mostly 'Chandler', but I could be wrong (I'm pretty sure at least the ones I ate were). There were a couple of flats that might have been 'Camarosa' or something like that. They were even more shameless than US strawberry packers in hiding the bad fruit under the good, probably because in an opaque container it's easier to hide).

Also, though not a fruit, I also sampled bundagi, silkworm larvae:

(I sampled some of these later, cooked not fresh, and wasn't too impressed, though my cousin told me the ones we had were not especially good ones...)