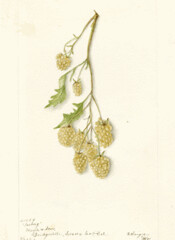

The Return of the Chestnut

If there were people other than me reading this page, some of them might complain that this isn't strictly a fruit post. To them I would say A) nuts are fruit, and B) it's my blog, and I make the rules. (I may eventually allow Mrs. Evil Fruit Lord to sneak some veggies on here at some point, so I might as well start pushing the envelope a bit anyhow).

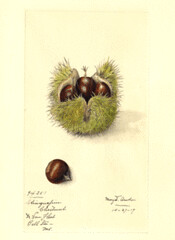

Most of us probably don't eat many chestnuts, but it wasn't so long ago that chestnuts, primarily gathered from the wild, were a major cash crop and food source for families in the Appalachians. The American chestnut (Castanea dentata), was once a major component of the eastern forests, often growing to a hundred feet or more. It also formed an important food source for wildlife and livestock, as well as valuable timber.

Most of us know the story of Dutch Elm disease. Not as many are aware that the same story has played out many other times as well. Butternut (Juglans cinerea), for example, is currently battling an imported fungus called Butternut canker which first appeared in 1967. In the case of the American chestnut, the attacker hitched a ride with nursery stock imported into New York in 1904, and by the 1940s Chestnut Blight had killed an estimated three billion trees. The once towering giants were reduced to understory shrubs, constantly suckering and dying back from the fungus.

There are still chestnuts around, of course, but in general these are its Asian and European cousins, which are resistant. The American chestnut has mostly dropped out of sight, except as the occasional diseased shrub. Eventually breeders began to work with chestnut, trying to breed trees which retained the character of the American chestnut, with resistance to the blight. Unfortunately, early breeders tried to do this by repeatedly crossing American chestnuts with Chinese, which resulted in blight resistant trees with a distinctly Chinese character. Later breeders have discovered the blight resistance is likely controlled by only two or three genes, and so by backcrossing to American chestnuts, they have managed to retain a large portion of the genes as American, while transferring resistance from the Asian species. A rare few American chestnut trees which escaped the blight have helped to maintain the genetic diversity of the seedling trees.

There appear to be a couple of organizations working to restore the American chestnut to our forests and yards. The American Chestnut Foundation and the American Chestnut Cooperators Foundation both support and perform research on blight resistance, and both provide American chestnut seeds and seedlings for planting. I'm really not clear on the differences between these two groups...they may be the same thing, or they may fight bitter chestnut research turf wars for all I know. The ACF has Jimmy Carter on their page, which scores points in my book. Either way, it's a noble cause. For Canadians, there's also the Canadian Chestnut Council, which conducts similar efforts north of the border, although I was disappointed to learn that unlike American cheese, which they call "Canadian cheese", they still call it the American chestnut.

Labels: American Chestnut, castanea, nuts

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home