Most of my "Fruit Genetics Friday" posts have really been basically genetics posts with a little gloss of fruit thrown in to tie them into the prevailing theme. So I thought for a change I'd do something very specifically fruit-focused, a little more of a story of breeding than a genetics lesson.

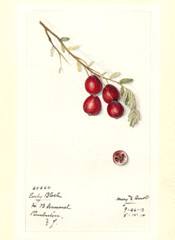

Currants and gooseberries are both members of the genus

Ribes, a group of fruit much appreciated in Europe but unfortunately often forgotten on this side of the Atlantic. I've heard a number of reasons suggested as to why

Ribes fruit haven't really become big players in the New World, despite successfully adopting nearly every other major European fruit, and having a selection of wild

Ribes of our own. I could (and, quite possible, might still) write a whole post on these, but I don't want to dwell on that in what is supposed to be a genetics post. Suffice it to say that if you're American and haven't had any of the fruits mentioned in this post, you're not alone. (But you

are missing out).

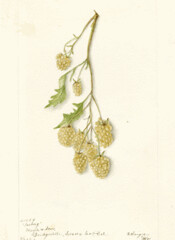

Given their obvious morphological similarities, the idea of crossing currants and gooseberries probably occurred almost as soon as people began developing intentional hybrid fruit. No doubt more than a few attempts were fueled by the gooseberry breeding craze which swept England in 1800's (a worthy subject for a later post).Perhaps the first was the product of a Mr. W. Culverwell, an Englishman who in 1880 produced what was called

Ribes culverwelli by crossing a black currant with a gooseberry. Producing hybrid seedlings turned out not to be too terribly hard, so long as the black currant was used as the female parent.

Such crosses yielded a range of diploid progeny, with a wide range of characteristics, some resembling their currant parent, some gooseberries, many somewhere in between. Unfortunately, they all had one thing in common: they were virtually sterile. Those that did set fruit did so parthenocarpically (ie, without fertilization) and so were dead ends when it came to breeding.

The Germans made some of the most concerted efforts, and in 1926 Paul Lorenz began making crosses at Berlin's Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. By World War II he had over 1,000 F

1 seedlings growing, but unfortunately in the chaos and destruction of the war, only eight plants remained. In 1946, these survivors were incorporated into a program at the newly founded Erwin Baur Institute.

It was there that Rudolf Bauer finally struck upon a method of generating fertile hybrids between black currants and gooseberries. By treating the sterile hybrids with a solution of colchicine, he was able to restore fertility.

Here I'll slip into a little more science: Colchicine is an alkaloid derived from autumn crocus (

Colchium autumnale) that has been put to a variety of uses over the years. Medically, it is used to treat both cancer and gout, although it's worth noting that it's teratogenic and widly toxic, two major downsides to any medicine (though manageable with adequate care). It's value in breeding was discovered in 1937 by Albert Blakeslee, who found that plants soaked in solutions of colchicine had multiple sets of chromosomes in their cells. Turns out, colchicine inhibits spindle formation during mitosis. So basically, the chromosomes double, but the cell fails to divide, resulting in a cell with double the normal complement of chromosomes.

This is pretty useful in and of itself: polyploid plants tend to be bigger, and that often includes fruit. Lots of crop plants are polyploid (the first Fruit Genetics Friday,

#1b, featured polyploidy, so I won't dwell on its many virtues here). However, from a plant breeding point of view it's greatest virtue is perhaps the ability to restore fertility in "mule" hybrids. It does this by providing chromosomes with a mate to pair with in meiosis.

For example: Imagine that a normal black currant or gooseberry has three pairs of chromosomes (they don't, they have eight, but let's keep this simple), for a total of six chromosomes. Each gamete (pollen cell or ovule) will have three, one from each pair, and these will combine to form a plant with the normal three pairs. However, the gooseberry and black currant have diverged enough evolutionarily that the chromosomes no longer recognize each other. Because of this, they don't pair normally during meiosis and can't form viable gametes. The result is a sterile plant.

So imagine the chromosomes as shown below ('c'-black currant, 'g'-gooseberry, '='-successful pairing):

Black Currant:

1c=1c

2c=2c

3c=3c

Gooseberry:

1g=1g

2g=2g

3g=3g

Diploid F1 Hyrbid:

1c 1g

2c 2g

3c 3g

The chromosomes in the hybrid don't match up, so they don't pair. Colchicine gets around this by providing each chromosome with a mate, its exact duplicate:

Tetraploid F1 Hyrbid:

1c=1c

1g=1g

2c=2c

2g=2g

3c=3c

3g=3g

Using this strategy, Bauer was able to improve the fertility of those eight survivors, and use them as the basis for further breeding. Although the collection was once again cut back severely when the institute moved to Cologne, he eventually generated 15,000 fertile tetraploid hybrid seedlings. From these he selected three hybrids, which he dubbed 'Jostaberry' as a group ("Josta" comes from the beginnings of the common names of both species in German,

Johannisbeere and

stachelbeere). However, there has been some confusion since then, and Jostaberry has been distributed as single clone, despite the fact that it was originally three distinct genotypes (two of which were siblings). It is not clear which of the existing clones are the original three (assuming all three survive). In addition to the original 'Jostaberry' introduction to the U.S., the Corvallis repository has two other clones, and a Swiss nursery has named two others of uncertain origin, 'Jostina' and 'Jogranda', so it's possible the originals are still out there.

The Jostaberry has much to recommend it (although it requires lots of pruning and does still suffer some residual problems with fruit set), especially in its resistance to white pine blister rust and its lack of thorns, and there has been a little subsequent interest in improving it. George Waldo, working with USDA in Oregon, did some further breeding, but there has been little activity since then, hampered by low yields and a limited market. In addition to the varieties mentioned above, the only other slections circulating are perhaps a dozen ORUS selections from the USDA, some of which are still available in nursery catalogs. Although a minor fruit today, it remains an example of what can be accomplished with a clever breeding strategy.

Labels: black currants, breeding, Fruit Genetics Friday, genetics, gooseberries, history, jostaberries, Ribes