A little while back, my two year old daughter and I were grocery shopping when she reached out of the cart and snagged a pear.

"That's a pear," I said, pointing to it.

"Parrot?" she replied. She has a puzzle with parrot in it of which she's rather fond.

"No, that's a pear," I said. "A Bartlett pear."

"Bartlett parrot," she said firmly, and cradled the pear lovingly against her chest. She refused to be parted from it from that moment on. The possibility of a brief separation at the check-out counter induced a bit of panic before the cashier's creative scanning technique averted disaster. She held it in the car, eventually falling asleep in her carseat with the thing still in a deathgrip in her little fingers. This is my daughter who eats no fruit at all unless tricked. I put baby and pear to bed together when I got home, and the pear briefly became a part of our family.

Luckily, she soon lost interest in her Bartlett parrot, who was starting to get a bit loved-to-death by the end, but it got me thinking just how surprisingly little I actually eat pears. I don't know why, but if I extrapolate from a small, highly unscientific poll of friends I can conclude that this is in fact the case with EVERYBODY IN THE ENTIRE WORLD. (Okay, so my methodology is a little suspect.) Anyway, I think pears tend to play the role of the forgotten little brother of the more popular apple. Everybody knows him: he's always around, he looks a lot like his brother, but nobody really bothers much with him. I could understand this with some of the other members of the family, like medlars or quinces. The average person on the street couldn't tell you what a quince looks like, what it tastes like, etc. But everyone, including people who never eat them, knows what a pear tastes and looks like (heck, we even use the term "pear-shaped" as a descriptor for all sorts of other things).

Pears once held a top spot in the pantheon of fruit. They are among the oldest cultivated fruits, dating back many thousands of years. In roughly 3,000 BC, a Chinese diplomat named Feng Li caused a scandal among his peers by ignoring his duties in favor of tending pear trees (versions of this story place it in 5,000 BC and include growing peaches...the details get a little muddy after a few millenia.) The pears Feng Li was tending were probably rather different than the "standard" pears, being "Asian Pears", probably of the species

Pyrus pyrifolia. The European Pear,

Pyrus communis is of somewhat uncertain origin, as much like its sibling the apple, it is quite possible it is a composite of a variety of local species, native to eastern Europe, Asia Minor, or the Middle East. Its history of cultivation is not quite as long as its Asian counterpart, but the pear has still been grown in Europe since at least 1,000 BC. Homer praised them as the "gift of the gods" in

The Odyssey in roughly the eight century BC, signalling the beginning of a long era of popularity for the pear.

The Romans, in particular, had a real passion for the fruit, and spent a great deal of time and effort studying its culture, classifying and identifying varieties, and spreading the trees to the far reaches of their empire. Pliny the Elder, in his

Natural History identifies the roughly forty varieties known to him in the Roman Empire (I say roughly, because I keep finding conflicting numbers...38, 39, 41. The only copy of this text I could come up with is in Latin, which doesn't help me. Anybody knows for sure, let me know.) A few hundred years later, Palladius lists 56. Most of these varieties are lost to us, or at least their identities are. Folks in Dark Ages Europe apparently had better things to do (like die of bubonic plague or kill each other in petty wars) than keep track of fruit varieties, and most of the Roman fruits appear to have lost any specific identity at that point in history. Still, at least a few existing cultivars are known to have come down to us from that era, and a few are specifically mentioned by Pliny or Palladius, such as 'Jargonelle', which was known to the Romans as Numidianum Groecum, and 'Petit Muscat', known then as 'Superba'. (A number of cultivars of ancient origin are preserved at the USDA germplasm repository in Corvallis, Oregon, which maintains an interesting page about some of them, including the equally ancient Asian cultivar 'Tse Li',

here.)

Like apples, pears today are vegetatively propagated by grafting to rootstocks, though chance seedlings found at one point or another in history comprise almost all of today's cultivars. Pear trees grow to a mature height of roughly 30 feet, but under normal culture practices are rarely allowed to exceed 18 feet or so (tree size can depend greatly on the choice of rootstock, training system, and pruning regime). The flowers are similar to that of the apple, and generally require a pollinator variety for fruit set. The fruit structure is similar to the apple, too, in that the flesh is mostly hypanthium fused to the ovary tissue. The gritty texture of pears is caused by hard, lignified cells called brachysclereids, though the degree varies between genotypes (Asian pears are less gritty and more apple like in their flesh...lots of folks like this about them, but I think it makes them more like bland, boring apples and less like pears). Asian pears are round, while European pears are, well, pear-shaped (the technical term is "pyriform", but that just translates literally to "pear-shaped", so why bother?).

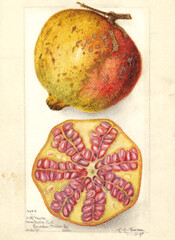

With all the similarities between the pear and the apple, it's not surprising to find the two are closely related. Both are members of the family Rosaceae, and are in fact members of the same subfamily, Maloideae (which they share with more obscure fruits including quince (

Cydonia),

medlar (

Mespilus), loquat (

Eriobotrya), and

mountain ash (

Sorbus)). Compared to apples, though, pears are more widely adapted, and on many farms have served to fill the corner of the orchard where other plants have failed to thrive, being more tolerant of shallow or poorly drained soils, even tight clay hard-pans. Pears tend to be longer lived and more productive than apples under the same conditions.

Early settlers in the America's brought both apples and pears with them from Europe, and early on the two enjoyed a rough parity in popularity, though both were consumed mostly in their liquid forms, cider and

perry. Pear production in the New World took a major blow, however, with the appearance of fire blight in the Hudson Valley of New York in the mid 1700s. The disease, caused by the bacteria

Erwinia amylovora (I wrote my M.S. thesis on it!) effects many Rosaceous crops, but none worse than the pear. By the time the efforts of breeders and modern chemistry had come up with ways of managing the disease, large scale pear culture was gone from the east. In the dry climates of the west, inhospitable to the bacteria and outside of its likely range, however, the pear thrived.

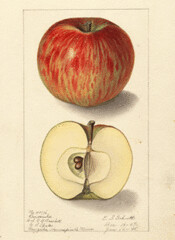

The top pear cultivars are all at least hundred years old, most much more than that. 'Bartlett', which accounts for roughly three quarters of American production, dates to at least the 17th century, when it was grown by a man named William Stair. Though he named the cultivar 'Stair', a horticulturist named Williams soon renamed it after himself. After a trip across the Atlantic, another enterprising nurseryman, Enoch Bartlett of Massachusetts, again renamed it, and, again, for himself. In fact, some people believe that the original 'Stair' was actually the pear referred to by Pliny as 'Crustuminum'.

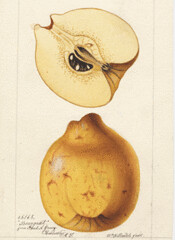

Following 'Bartlett' in the rankings are 'Anjou', 'Bosc', 'Comice', and 'Kieffer', all of which are well over a hundred years old. The last is in fact a hybrid of

P. communis and

P. serotina, the Chinese Sand Pear. While it's popularity has waned somewhat, 'Kieffer' was introduced in 1876 and enjoyed a good run despite unimpressive fruit quality due to its superb resistance to fire blight, and remains common canning variety.) Red sports, or mutations, of many of these cultivars exist and can often be seen in the market. (

USA Pears maintains a nice little site with information about the common varieties.)

It's striking to me how little impact modern breeding has made on pear cultivars. Looking at the list of the top nine cultivars grown in the U.S. in 1993 (If you're interested: Bartlett, Anjou, Bosc, Comice, Kieffer, Clapp's Favorite, Seckel, Hardy, and Winter Nelis), every single one is listed as a major cultivar grown in California by Edward Wickson in his book,

California Fruits (my edition is dated 1914), and even he notes that Bartlett completely dominated the market in that era as well.

Maybe that's because the current pears are just so darn good. Or maybe it's because nobody is eating them anyway, though I suspect some one must be buying them, despite the striking survey results. They're on my next grocery list.

(By the way, I'm sorry there isn't more on Asian pears in here: I don't know as much about them and I don't like them as much. But, to be fair, it must be said that they are the hot new thing in the U.S. these days, and are being planted in impressive numbers and sometimes even sold for even more impressive prices. I think they remind me of a potato dipped in pear juice and disguised as an apple. But that's just me. If anyone is dying to hear more on them, I'll drag out the file and write something.)

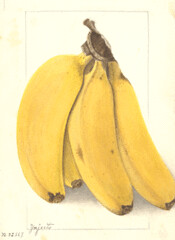

Update: I switched the "Fruit Image of the Day" from 'Kieffer' (which was a recycled image from earlier, anyway) to 'Bartlett', from the National Agricultural Library's collection of pomological watercolors. The full online collection of pear paintings is

here. Some truly beautiful artwork.

Update 2: My nifty 'Bartlett' image looked like hell at that particular size, so I scaled it down so it's pretty again. I don't know why it looked so bad that big (the original is much larger than that). Oh well.

Labels: pears, Pyrus