I feel an unusual fondness for elderberries, considering that I've never grown them nor I do eat them particularly often. I suppose I'm not entirely unique in this respect, as plants of the genus

Sambucus have long been revered by a number of cultures. Supposedly to this day there are places in northern Europe where some men still doff their hats when passing an elderberry bush, traditionally considered the home of spirits (granted these may well be crazy old men for all I know, but it's kind of a nice tradition).

There are a lot of non-spiritual reasons to like elderberries, too. On a personal level, they remind me of when my uncle, car broken down at the side of road at the and waiting for a tow, discovered elderberry plants at the edge of the woods, heavy with fruit, and proceeded to load up on as many as he possibly could, taking cuttings from the plants for good measure. We planted the cuttings (they root easily, just dusted them with rooting hormone and stuck them in a bucket of sand) and made wine from the berries. The pure elderberry wine was pretty good, but the wine from 4/5 NY73.0136.17 grape juice blended with 1/5 elderberry juice was absolutely wonderful.

They also remind me of when a former co-worker of mine once brought in an elderberry pie, which we ate during coffee break one friday morning. One small problem: she didn't realize she needed to add sugar. Elderberries are not a sweet fruit. When my uncle and I made wine with them, I think the sugar levels came out at at about 1 Brix (compare to 10+ for almost all ripe fruits you eat fresh, and 20+ for most grapes). The pie was nearly inedible, but we all worked our way painfully through it until she finally sat down to try her own piece, at which point we were immediately instructed to stop eating and showered with apologies.

With the correct sugar added, though, they do make a good pie, as well as jelly. There's some interest in them as a 'nutraceutical', being extremely high iron, among other things, and the juice can be used as a dye. And they're easy to grow and quite productive, with very few pests or diseases, although they have real problems with viral diseases some places and occasional troubles with powdery mildew. They're widely adapted, with a native range covering most of the U.S. and Canada. The plants are quite attractive (there are even some ornamental cultivars), and don't mind partial shade as far as I can tell. I recently read that they seem to tolerate juglanone, the toxic substance secreted by the roots of black walnut (

Juglans nigra) and butternut (

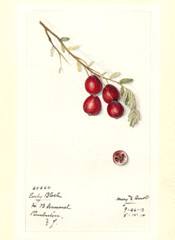

Juglans cinerea) trees, so perhaps they're a good use of the shady empty space under such a tree. They're fast-growing tall shrubs, ranging up to 12 feet high, with very pretty fragrant flowers and a handful of long canes. The clusters of zillions of shiny berries look quite tempting when ripe, though they turn out to be disappointingly tart (some types are sweet enough that I enjoy them fresh, but my wife assures me I'm weird in this way.) The native Americans used it both as food and as a mild laxative and treatment for measles.

On another personal note, every time I think about a fruit in which little breeding has been done, I get a little surge of excitement thinking about the possibilities, and elderberries certainly have not been bred very much. A survey of planting recommendations will turn up a list of the same five or so cultivars every time: 'Adams No. 1', 'Adams No. 2', 'Johns', 'Nova', and 'Scotia'. The first, and for a very long time, only player in the not-so-competitive world of elderberry breeding was the Cornell, at the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station. This program released two cultivars in 1926, on behalf of a Mr. Adams, but apparently could only come up with one name, resulting in 'Adams No. 1' and 'Adams No. 2'. (An old flyer for 'Adams Improved Everbearing Elderberry No. 2' is viewable

here.) For a good thirty years or so, this was it as far as named cultivars. The Kentville, Nova Scotia station got involved at that point, first naming and releasing 'Johns', a wild selection which had been in wide cultivation for some time, and then a series of releases in 1960: 'Nova', 'Scotia', 'Kent', and 'Victoria'. All of these, I believe, are open pollinated selections from 'Adams No.2'. 'York', Cornell's third and final release, is a cross between 'Adams No. 2' and 'Ezyoff' (another cultivar which seems largely forgotten), so the currently available named varieties are highly dependent on a single genotype. (I've often though it was too bad that after 'Nova' and 'Scotia' from Nova Scotia, the Cornell program didn't pair 'York' with another cultivar named 'New'.)

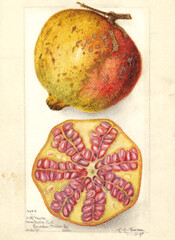

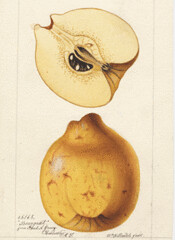

It seems as though there would be plenty to work with if some one did feel inclined to breed them. The genus

Sambucus contains a number of species with a wide range of traits.

S. nigra, the European Black Elderberry, and

S. canadensis, the American Elderberry are the two most commonly cultivated for fruit, although others are edible. There's quite a range of traits available, with striking variability in fruit and leaf color, as well as in fruit and cluster size. I think there is some breeding for ornamentals going on, given the appearance of a few new ornamental cultivars in recent years, but I think both Cornell and Kentville have been out of thre breeding game for quite a while. East Malling Research in the U.K. appears to have a program, releasing 'Gerda' and 'Eva' in recent years (sold as 'Black Beauty' and 'Black Lace', respectively), but these appear to have been selected primarily for appearance, not fruit.

If I ever have tons of land, which is looking a tad unlikely, I'd probably take a crack at it. Still, they're nice enough looking that I'll probably throw one or two in the yard once we finally get settled somewhere.

Labels: breeding, elderberries, sambucus