John Schmid:

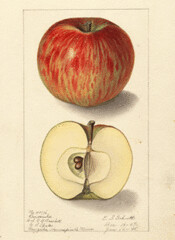

The Hunt for an Improved Melrose, pt. 2

And now the exciting conclusion...

When full production began in our special orchard at Jackson, it soon became clear that no tree stood out as being as superior as the russetted trees were bad. We had to depend on statistics and the computer to choose selections.

Each year yield records were recorded and a 10 fruit sample from each tree was brought to Wooster for evaluation. We were looking for better color, but any improvement would be welcomed, so the data we collected was average fruit weight, length/width ratio, color intensity, percent color, firmness, soluble solids (sweetness), and since russet was a problem some years, a russet rating. Over the next five years, this fruit evaluation made up a large part of my winter’s work.

When the evaluation was over, we made eight selections based on computer analysis that scored better than the standard ‘Melrose’ in color, percent color, and yield. We found no selection that was superior to the standard in any other measurement.

During the years of this study other, better coloring strains of ‘Melrose’ had been identified in France and England. We obtained trees of each and had grown them in our orchards at Wooster.

A commercial grower in Ohio found a sport of ‘Melrose’ in his orchard that seemed to be a spur type. We were able to obtain bud wood and propagate trees of this strain. (A “spur type” has shorter internodal lengths, thus having the advantage of growing more fruit in a given space.)

At this point we were ready for a replicated trial. We propagated our eight selections, the two from France, the three from England, our Ohio spur type, and standard ‘Melrose’ as the control. An orchard was planted at Wooster consisting of six trees of each.

Once more yield records were taken each year. Again 10 fruit samples were taken and data collected. After ten years and six years of fruit data the experiment was finished and all data was submitted to computer analysis. The summer of 2000 was my chance to announce the results to the world, well, to the Ohio fruit growers that attended the Horticulture field day at Wooster, Ohio.

Some of our eight selections were slightly better in color than standard ‘Melrose’, but not as good as the French strains, ‘Melrouge’ and ‘Melred’. In all other measurements, none of the selections or strains was better than the standard.

If you plant ‘Melrouge’ or ‘Melred’, you will get a slightly better colored ‘Melrose’ in most years. Sorry, just an incremental improvement; no real scientific breakthrough here.

The spur type? Well, it turned out to be a true spur type. Want to plant it? I wouldn’t recommend it. The spur type averaged less than one apple a year per tree in our trial.

. . . so much for nearly 25 years of research. I use this as an object lesson for why there are fewer and fewer tree fruit breeding programs at our state universities. You are not guaranteed success, no matter how much time, effort, and resources you bring to the program.

When it was first introduced, there was great hope for mutation breeding. Lots and lots of cuttings, budwood, and seedlings got irradiated, dipped in mutagens, etc. In the end there was comparatively little to show for it. There were a few success stories (the self-compatible sweet cherry, for example, as well as some growth habit mutants in tree fruit), but for the most part the mutants it generated were of limited utility. And when you think of it, it's not that surprising. Mutation breeding is a little like trying to fix a watch by hitting it with a hammer. Much of the time, it'll just break completely. Some of the time it'll keep running, but not as well as before. And sometimes, very, very rarely, there is a tiny chance that it might actually work better. Breaking chromosomes is no different.

That said, given the track record of natural mutant sports in apple, fruit color is probably as good a target for mutagenesis as any trait, since single locus mutations can clearly have a profound effect on fruit color.

Labels: apples, breeding, John Schmid, malus

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home