Poking through food blogs today, I came across

this at

The Scent of Green Bananas. I'm not as into food blogs as many of my readers here (I have a few I visit regularly, but many just sort of blend together for me), but I think I really like this one and will probably add it to my regulars. She's got a number of interesting fruit posts (for instance

atis and

mangosteens) that occasionally remind me of my own (except with better photos and better writing and less horticultural stuff).

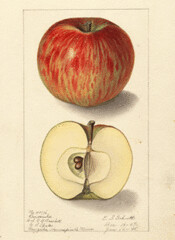

Anyway, I came across the persimmon post, and, not surprisingly, reading about persimmons got me thinking about persimmons. I like persimmons. I don't eat them often, usually just in small amounts in Japanese food. I rarely eat them fresh and whole, which is too bad because a truly ripe persimmon is a wonderful thing (I once bit into a not remotely ripe American persimmon, a horrifically not-wonderful, astringent experience). I have to admit, as irrational as it is, part of the reason I like persimmons is that they look kind of like big tomatoes.

There are an assortment of persimmon species, all belonging to the genus

Diospyros, which it shares with ebony.

Diospyros is one of only two genera in the family Ebenaceae, but it's a big one, roughly 500 species. The genus name comes from the greek

Dios pyros, meaning "Fruit of the Gods", which was the ancient Greek name for the date-plum,

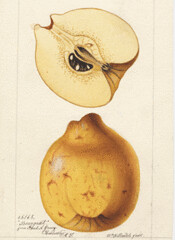

Diospyros lotus. Most persimmons, basically all the ones you might find in grocery store (unless your grocery store is very different than mine, which some are) are the Japanse Persimmon,

Diospyros kaki. 'Kaki', incidentally, is the Japanese name for the fruit. It's a native of east Asia (though probably not Japan, originally) but is grown quite a fair bit in the U.S. and southern Europe these days, though China, with nearly two thirds of world production, is still the big player in the persimmon world. There are two major types available in the U.S., the 'Hachiya' and 'Fuyu'. 'Hachiya' is the more common, but 'Fuyu' is non-astringent and has been rapidly gaining popularity.

Japanese persimmons fall into four basic categories: pollination constant non-astringent (PCNA), pollination variant non-astringent (PVNA), pollination constant astringent (PCA), and pollination variant astringent (PVA). Astringent vs. non-astringent refers to the character of the fruit before completely soft, and pollination constant vs. variant refers to whether the fruit is influenced by pollination or not (poorly pollinated PV types are light in color and remain astringent even when ripe). Obviously, PCNA-types are the prefered cultivars in most cases.

Although

D. kaki is the major persimmon species, there are a handful of other edible ones.

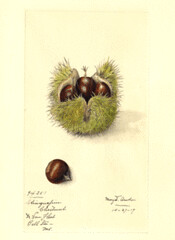

Diospyros virginiana, the Common or American Persimmon, is native to the eastern U.S., from Rhode Island to Texas. It's not really commercially cultivated for the fruit, though it's actually pretty good, but the wood is utilized for a variety of specialty purposes, like golf clubs and pool cues. It's also the source of the name, from the Algonquin word 'pessamin', meaning "dried fruit". The persimmon features in a number of Native American legends, and was a favorite of both natives and settlers alike, as it stored well and can be harvested when completely ripe by merely shaking the tree.

There's also

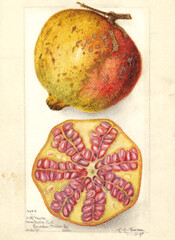

D. discolor, the mabolo or velvet-apple, a native of the Philippines. I honestly don't know much about it, though apparently it smells like cheese and some folks really like it. (I think that's it for edible persimmons, but with 500 species, I can't say for sure...let me know if I've missed any.)

Only the Japanese persimmon has been extensively bred, primarily in Japan and China, although a few other countries have developed local cultivars, such 'Kaki Tipo' (Italy), 'Lama Forte' (Brazil), and 'Triumph' (Israel). It's a hexaploid, which somewhat complicates genetic studies, but much progress has been made. The other species have mostly been the realm of hobby breeders, though at least one,

James Claypool, made a serious effort to improve the American Persimmon, and his program is being continued by the

Indiana Nut Growers Association.

Bud mutation, and through it the formation of

chimeras, is an important form of variation in persimmon breeding. At least half a dozen cultivated clones originated as mutations of 'Fuyu' alone. The other major issue in persimmon breeding is the exteremly narrow germplasm base for PCNA cultivars, the most desirable type. In the over a thousand named cultivars at the turn of the century, only six distinct cultivars were known to be PCNA-types, all Japanese,the earliest being 'Gosho', dating to the 17th century. A handful of others have been discovered since, bring the total to about 18, including one from mainland China. Efforts to breed more PCNA cultivars have been successful, but the inheritance of the trait is uncertain (and the hexaploid nature of the species complicates inheritance studies), and the limited germplasm base is still worrisome, as this tends to leave crops vulnerable to emerging pest and disease threats and may limit an industry's ability to adjust in the face of such challenges. (This is an issue with far more crops than just persimmons, and I intend to write more on it in the future.)

Update: As is always the case, I posted this thing and immediately found a link I should include.

Slow Food USA Ark of Taste has a great page on the American persimmon

here.

Update 2: As if by magic, as soon as I put up a persimmon post, the discussion on the NAFEX mailing list turns to persimmons, and I thought of at least one more edible species that I really should have remembered:

Diospyros digyna, a Mexican species with fruit that looks and tastes (at least vaguely) like chocolate pudding, hence it's common name, the Chocolate Pudding Fruit. (Its other name is Black Sapote, which I've actually heard more often.)

Looking that up, I also noticed that I appear to have neglected

D. mespiliformis (Medlar-shaped persimmon?), aka the Jackalberry, a native of Africa, and

D. montana, the mountain persimmon, native to the Americas. I honestly don't know much about these, but there they are, for completeness sake.

Labels: Diospyros, persimmons