John C. Schmid: Scientific Breakthrough, Fire Blight

Another piece from my occasional contributor and retired Ohio State researcher, John Schmid:

One of the first things I learned when I became a technician in the Horticulture Department was just how devastating fire blight can be to apple trees and apple orchards. In the following years I tried to learn as much as was known about the disease.

I learned bacteria that are normally found in orchards cause fire blight. The bacteria can enter a tree through the pollen tube of an open flower during bloom, at the tips of growing shoots, through wounds such as from hail or careless mowing, or less likely, by bark beetles boring into the trunk.

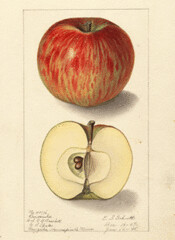

Cultivars and rootstocks differ in their susceptibility. 'Jonathan', 'Rome', and 'McIntosh' are very susceptible to fire blight, while 'Delicious' and 'Golden Delicious' are very resistant. Susceptible rootstocks, such as M.9 are vulnerable to fire blight strikes to root suckers. This can leave you in the unenviable situation of having the cultivar untouched by disease; but with the roots, killed by the bacteria, the tree dies.

Yet, much remained unknown. Antibiotic sprays seemed of some help in preventing outbreaks, but were expensive and had to be applied multiple times during the spring. They also had to be applied every year because no one could predict when infections were likely and they proved to be of little use after an outbreak started.

Young orchards, in their third or fourth year were often struck when just coming into production. The grower is left with no income to offset the cost of establishing, training, and maintaining the orchard through the early years.

Twice in my years at Wooster, southern Ohio growers lost their apple crops to a late spring frost or freeze. We sympathized with them even more as the next year brought horrendous outbreaks of fire blight. It was just one thing after another for those unlucky growers.

Skip ahead a few years. Dr. Ferree and his graduate student, James Schupp (now Dr. Schupp at Penn State U.), and I decided to stop by the small orchard where Jim had his research. The experiment was in its third year and involved taking physiological measurement on 'Golden Delicious' trees that carried differing crop loads. The treatments included the extremes; no thinning at all on one end and no crop, achieved by complete flower removal on the other. These treatments had been applied to the same trees for three consecutive years.

We had just gotten out of the car when we noticed that trees scattered throughout the orchard were dead, all the foliage was brown and still clinging to the branches, a sure sign of fire blight. Incredibly, the trees around them were completely untouched. We were shocked, the trees were all 'Golden Delicious'; it was rare to even see a small fire blight strike on a 'Golden Delicious' tree.

Jim quickly checked his treatment map. All of the dead trees were of one treatment; complete flower removal.

The thunderbolt hit! Everything clicked into place. Discussing it later, it was the same for all of us. I honestly can't say who mentioned what or when, but here is what we all knew in an instant and quickly discussed among ourselves.

Removing a crop for three consecutive years caused a build up of carbohydrates in the tree with no place to go. Excess carbohydrates are normally stored in the roots, but the storage capacity of the roots had been overwhelmed. I had assisted Jim in collecting data on this experiment in previous years. We had already noticed that the leaves of this treatment were much thicker, almost leathery. He had documented the increased dry weight. Now we knew the excessive carbohydrate levels throughout the tree was providing a wonderful growth medium for the fire blight bacteria. Much like diabetes in humans causes an increased risk of infection.

Young trees in their early years, growing fast without a crop would also have an increased carbohydrate level and account for their susceptibility to fire blight.

The southern Ohio crop loss to a late frost or freeze sets up the next spring's fire blight outbreak in the same way.

James Schupp in the next few weeks prepared a "note" for the Journal of the American Horticulture Society. The rest of the summer he did further research for a full paper on the subject in addition to finishing his work on the original project. The most memorable aspect of this study to me was the electron microscope photo of a cell so full of carbohydrate inclusion bodies that the cell wall had ruptured, death for the cell and a sure feast for bacteria.

This was truly a scientific breakthrough, one of the few that I saw in all my years in research. A quote by Louis Pasteur seems to be appropriate at this time: "Chance favors the prepared mind". Like many scientific breakthroughs, this was a case of pure serendipity; it was not what we set out to discover. It truly was a "bolt out of the blue",a true scientific breakthrough.

I worked with fire blight on my M.S. thesis, but in a realtively obscure context: blackberries. I'm the proud author of roughly a quarter of the literature on the fire blight in brambles (much more if you count the thesis). On apples, and pears, however, it's a major problem, and this discovery marked a significant step towards understanding the factors influencing resistance.

Labels: apples, John Schmid, malus, pathology

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home