A pollinator shortage?

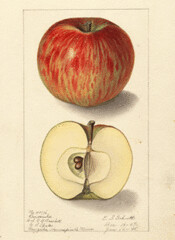

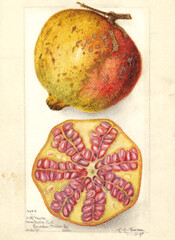

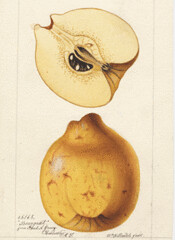

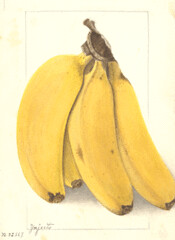

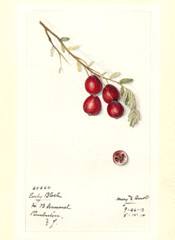

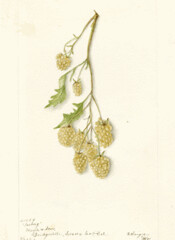

The average person probably associates bees with honey (or maybe stings) more than they do with fruit, but the fact is that the production of many fruit species is highly dependent on bees. Many of the tree fruits, being self-incompatible, are highly dependent on pollinators and would set virtually no fruit without them. Even many self-fertile fruits would see a notable decrease in yield with insect pollinators.

In some cases, growers will bring in hives specifically for pollination, in others, farmers depend on natural populations of pollinators. Neither is quite as easy as it once was. Honey bees, in particular, have been hard hit of late. Beginning in England in the early 1920's and appearing in the North America by 1980, the tracheal mite was the first wave of the attack. The microscopic mite resides the bee's windpipe, where it feeds and reproduces. Female young climb out and onto the ends of the bee's hairs, where they are spread by contact with other bees. Affected bees are weakened, though it may take an outside stress such as another disease or poor weather before large scale damage results.

The next threat was also a mite, but this was much larger, external, and visible to the naked eye. Image a parasite about the size of a grapefruit attached to you. That's the Varroa mite, Varroa destructor (the name sounds like something from a bad action cartoon). A native of Asia, it had already been a problem in Europe for a while before it made it here in 1987. It weakens the adults and often kills the larvae, and can vector viral diseases. Losses may be as little as a few percent of the hive in the first year or two of infestation, but often increases to as much as 100% in just a few years. Damage has been severe in many cases. Almond growers, who require pollinators for fruit set, recently imported foreign bees for the first time since 1922 (when the practice was made illegal to avoid the import of tracheal mites, incidentally) because domestic populations were too limited.

Progress has been made on chemical controls for both of these, though none are entirely satisfactory, and in many cases infestations may go unnoticed until serious damage has already occurred. Resistance is already showing up to many of the treatments. Some progress has been made in using Asian bee species, which co-evolved with the mite and have developed grooming behaviors to remove it. But while these things may hold some hope for domesticated bees, it provides little help for the native populations, which have also been severely affected by the mites.

The National Academies of Science are issuing a report looking at the status of pollinator species and the reason for their decline, though the report hasn't been published yet. (People with $50 to blow on it can get a prepublication uncorrected copy here. I am not one of those people.)

Labels: pollination

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home